Links

- CV

- Titles

- Topics

- Tickets

- Science

- About Eric

- Book Reviews

- Country Profile

- Modern China

- Contact Eric

- Podcast

- Vision

- Sekai

- John

Archives

RSS

Reflections on a Wandering Life.....

Sunday, June 26, 2016

The Jessup

The way it works is that teams are matched against each other in 90 minute rounds. Each team puts up three contestants for each round, but only two of them speak. The third is considered "of counsel." So for each round, there are two applicants and two respondants, and each team gets 45 minutes. They generally reserve one or two minutes for rebuttal. During their presentation of their pleadings, the judges on a three-judge panel will ask them questions, just as any panel of judges would do, whether in a court of appeals, the US Supreme Court, or the ICJ itself.

Click for larger image.

The judges for the national competition are typically professionals from the legal community who volunteer to serve as judges for the contest. The case is not real, of course. It is a ficticioous case designed to give approximately equal arguments to both sides, and is outlined in detail in a document called the "compromis," which is usually influenced by current events in the arena of international law. So the compromis contains the "facts" of the ficticious case, and students are expected to apply existing law (such as previous decisions by the ICJ) in arguing their respective positions. This exercise gives them a chance to show their knowledge of the facts, as well as relevant law. This is an important exercise for young lawyers. Many years ago, when I was a senior in high school, I served on a jury in a moot court case at Willamette University Law School. The case in that moot court was a traffic case. I remember the law student playing the role of the prosecutor announced to everyone that he had been a police officer and launched into an impassioned defense of the law that had allegedly been violated. The judge looked at him and said, "Your entire line of argument is irrelevant The question before the court is not about whether this law is good or not. The question is whether or not the law has been violated by this person in this instance." So it's important for young lawyers to be aware of both the facts and the law.

The judges for the national competition are typically professionals from the legal community who volunteer to serve as judges for the contest. The case is not real, of course. It is a ficticioous case designed to give approximately equal arguments to both sides, and is outlined in detail in a document called the "compromis," which is usually influenced by current events in the arena of international law. So the compromis contains the "facts" of the ficticious case, and students are expected to apply existing law (such as previous decisions by the ICJ) in arguing their respective positions. This exercise gives them a chance to show their knowledge of the facts, as well as relevant law. This is an important exercise for young lawyers. Many years ago, when I was a senior in high school, I served on a jury in a moot court case at Willamette University Law School. The case in that moot court was a traffic case. I remember the law student playing the role of the prosecutor announced to everyone that he had been a police officer and launched into an impassioned defense of the law that had allegedly been violated. The judge looked at him and said, "Your entire line of argument is irrelevant The question before the court is not about whether this law is good or not. The question is whether or not the law has been violated by this person in this instance." So it's important for young lawyers to be aware of both the facts and the law.

Last year, the compromis told a story about secession, and was obviously based in the situation in Crimea. This year, the Compromis addresses cyber spying and was strongly influenced by Edward Snowden and Julian Assange. This year's compromis was written by Asaf Lubin, former intelligence analyst for the IDF. The video below includes includes a question from one of our students about how the compromis came to be written, and I liked Asaf Lubin's answer. I was also intrigued by what he said in his introduction about the presumption of lawlessness in the area of espionage. I agree with him, but I don't know how this issue can be resolved. Can anyone imagine a world where spying is a violation of international law, and every country signs off on it? Or can anyone imagine a world without espionage? Is there even such a thing as lawful espionage?

Last year, the compromis told a story about secession, and was obviously based in the situation in Crimea. This year, the Compromis addresses cyber spying and was strongly influenced by Edward Snowden and Julian Assange. This year's compromis was written by Asaf Lubin, former intelligence analyst for the IDF. The video below includes includes a question from one of our students about how the compromis came to be written, and I liked Asaf Lubin's answer. I was also intrigued by what he said in his introduction about the presumption of lawlessness in the area of espionage. I agree with him, but I don't know how this issue can be resolved. Can anyone imagine a world where spying is a violation of international law, and every country signs off on it? Or can anyone imagine a world without espionage? Is there even such a thing as lawful espionage?

When the Americans realized they needed intelligence during World War II, they set up the OSS under Colonel (later General) William J. Donovan.

Later the OSS set up a "Research & Development" branch, with Stanley Lovell as its first director. In his 1963 memoirs, Lovell wrote that his goal was to "stimulate the Peck's Bad Boy beneath the surface of every American scientist, and to say to him: 'Throw all your law-abiding concepts out the window. Here's a chance to raise merry hell.'" The OSS came up with some wild ideas. They had a plan to lace Adolf Hitler's food with female hormones so that he would develop a high voice and lose the respect of his officers.

The OSS was disbanded after World War II, and the CIA was eventually established to take it's place. Eisenhower is known as a "peaceful president," because he ended the Korean War and presided over an America that was uninvolved in military conflict for the remainder of his presidency. But the covert picture was quite differnt. Eisenhower used the CIA to remove foreign leaders that he didn't like--most notably Mohammad Mosaddegh of Iran, which action created a hostility that has endured to the present day. To this day the U.S. has no diplomatic relations with Iran and does not have an embassy there.

Later in Eisenhower's presidency, the CIA developed plans to assassinate Fidel Castro of Cuba. This folly continued into Kennedy's administration, so it is evident that both Eisenhower and Kennedy wanted Castro dead. Most of their schemes were poorly conceived, and none succeeded. They actually convinced a New York City police officer to give Castro a cigar filled with enough TNT to blow his head off. Would have made an interesting headline (no pun intended), but apparently the cop was never able to get close to Castro.

In 1962, the Joint Chiefs of Staff hatched a plan to have the CIA commit acts of terror against US citizens, which would be blamed on Cuba, and used to justify going to war against them. Fortunately Kennedy nixed that one.

More recently, the CIA has come under much controversy, because of the exponential increase in drone strikes under Obama. Leon Panetta, former director of the CIA relates a situation where he was at Arlington National Cemetery attending the funeral of a CIA officer who had been killed by a terrorist in Afghanistan. Suddenly he got a call saying that the CIA had the terrorist in the crosshairs of a drone. The only problem was that his family was with him. Panetta had to make a decision right then and there about what to do. In the end, he gave the green light, and the terrorist was killed, along with his wife and children. This decision was made by an appointed cabinet level official completely outside the chain of military command.

So I applaud Asaf Lubin for going after this issue, and wish him well. But I'm just not sure how optimistic I can be. Espionage of some kind seems inevitable in a sinful world. And how can it ever be made lawful? What country would agree to terms by which an enemy nation could legally spy on them? Lubin himself alludes to this in his own closing remarks at the end of the video, when he quotes from the The Secret Pilgrim, by John le Carre:

For as long as rogues become leaders, we shall spy. For as long as there are bullies and liars and madmen in the world, we shall spy. For as long as nations compete, and politicians deceive, and tyrants launch conquests, and consumers need resources, and the homeless look for land, and the hungry for food, and the rich for excess, your chosen profession [intelligence analysts] is perfectly secure, I can assure you.Anyway, the video is a bit long, but parts of it are useful if you are interested in international law.

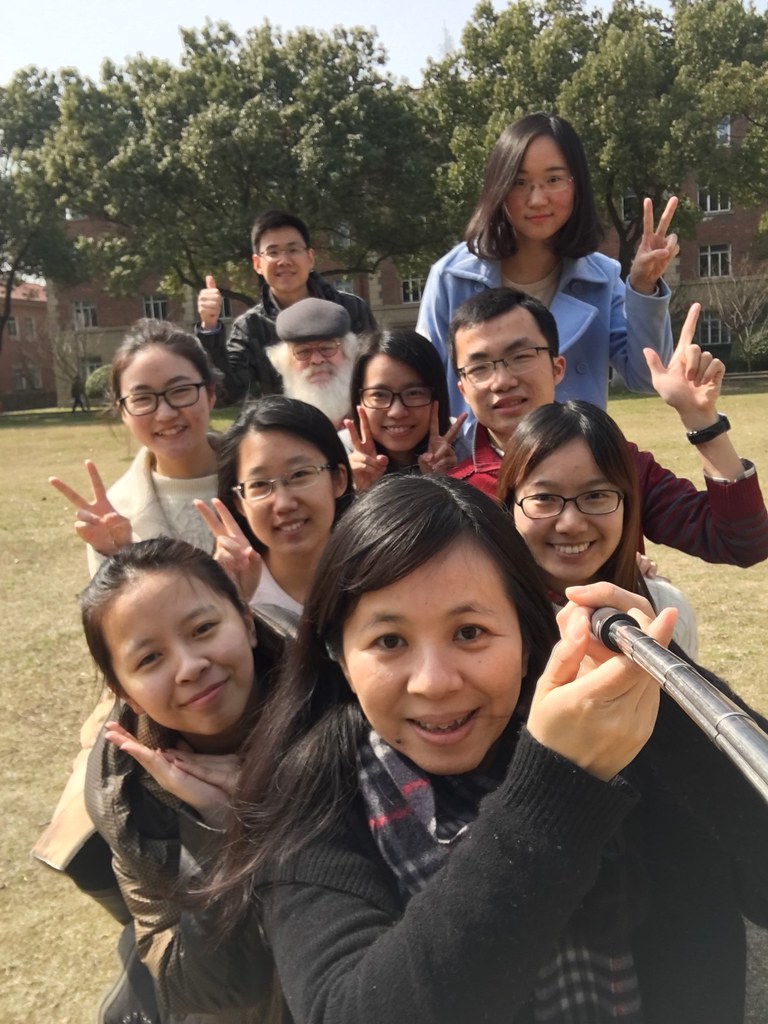

During the Jessup competition, the presentations by the students are usually very serious and professional, but on the last afternoon of the preliminary rounds for the China national competition in Suzhou, there was an amusing moment when one of the contestants for the other team was presenting her argument, and she cited a case which, according to her, had been appealed all the way to the Ninth Circuit. She was obviously unaware that the presiding judge for that round (seated, center) is actually a federal judge on the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals. He smiled when she said that, but it went right by her, until the end of the round, when the judges introduced themselves. Judge O'Scannlain had to leave China early because of an emergency. He was a close friend of Antonin Scalia, and had to fly back to Washington for the funeral. But he stayed through the preliminaries, and judged many rounds. The Jessup could not exist without the kindness of people like Judge O'Scannlain.

The judge who asked some of the best questions, I thought, was a retired trial judge from Hawaii (seated, right). He had been a trial judge for 25 years and a trial lawyer before that for just about as long. I think he had also been a JAG officer in the military, so he had a lot of experience. But he really put those kids to the test. The judges asked pretty tough questions during the rounds, but they were quite conciliatory in their remarks at the end of the rounds, because they understand that these young people are learning.

The CYU team has an advantage, because they have the assistance of Professor Shinye Murase (standing, front and center, with me and the team members) from Sophia University. He has written an International Law text which has recently been translated into Chinese by a member of our faculty, and he has volunteered to help coach our team. But we also benefitted immensely from the tireless efforts of Dr. Chen from the law school (holding the stick for the super-selfie), the head coach of the CYU team. And the team members have gotten much good advice from Professor Bramwell Osula, a member of our faculty who used to teach at Regent University in Virginia Beach. Unfortunately, Bramwell was in the States giving a lecture or something, so he was not able to go to the national contest.

The CYU team has an advantage, because they have the assistance of Professor Shinye Murase (standing, front and center, with me and the team members) from Sophia University. He has written an International Law text which has recently been translated into Chinese by a member of our faculty, and he has volunteered to help coach our team. But we also benefitted immensely from the tireless efforts of Dr. Chen from the law school (holding the stick for the super-selfie), the head coach of the CYU team. And the team members have gotten much good advice from Professor Bramwell Osula, a member of our faculty who used to teach at Regent University in Virginia Beach. Unfortunately, Bramwell was in the States giving a lecture or something, so he was not able to go to the national contest.

We have seen excellent progress from our team in the last two years. Last year they came in 17th out of 40 or 45 teams. This year they were eighth. Only the top five teams go to Washington for the International finals, so they were not be part of that, but they were invited to D.C. anyway as an exhibition team. Last year, in Washington, they won two and lost two. This year they cleaned house. They went up against teams from Egypt, Russia, Italy, and Bulgaria and won all four rounds.

Saturday, April 2, I got up at 2 o'clock in the morning to watch the final championship round livestreamed from Washington (There's a twelve hour time difference between Beijing and Washington). The final round was between an American team and a team from Argentina. The Americans were very good, but I thought the Argentines were better, and I was not suprised when the judges gave it to them. During the final round, Sir Christopher Greenwood was questioning one of the American contestants about interpretation of law, and he said, "Thou shalt not commit adultry" can be interepreted several ways but it cannot be interpreted as "Thou shalt not commit adultry, but in fact, adultry is quite alright." I wish he could give that admonition to the members of the American Supreme Court.

It's a little sad to watch the losing team stand by as the winning team gets the all the glory. You don't get to the finals without being very good. All of those contestants in the final round have the potential to be world class litigators. But I do have to say the Argentines deserved to win. They were quite impressive.

There is so much injustice in this world. So much that is not right. When we are reminded of this reality, it can either drive us to despair, or move us to work together to train young people to fight for justice for those who have no one to speak for them. The Jessup has become a very important part of that mission.

Labels: Espionage, International Law, Jessup